Wage transparency works

New research shows that the much-discussed measure of requiring firms to disclose gender segregated wage-statistics to clarify differences in women's and men's wages reduces the pay gap by 7%. An important step in the right direction and knowledge that can boost the ambition to ensure women the same pay for same work, researchers say.

Women are paid less for the same work as men in the labor markets of most developed countries. When a man earns 100 dollars, a woman earns 78.5 dollars in Germany, 79 dollars in the UK and 83.8 on average across EU-countries according to 2016-statistics from Eurostat.

Women are paid less for the same work as men in the labor markets of most developed countries. When a man earns 100 dollars, a woman earns 78.5 dollars in Germany, 79 dollars in the UK and 83.8 on average across EU-countries according to 2016-statistics from Eurostat.

Reducing the gender pay gap has been at the epicentre of a heated debate among academics, policy makers and unions for years, and legislation that require employers to publish gender-based wage-statistics to provide pay transparency has been proposed nationally and internationally in the belief, that this would promote equal pay.

Opponents of pay transparency have argued that disclosing gender differentiated pay statistics increases the administrative burden of firms, violates employee-privacy and confidentiality - and that the effect of all this hassle is unclear or even non-existing.

But new research shows that pay transparency has a positive impact on closing the wage gap. Economists from universities in Denmark and the US, who have examined the effect of a 2006 requirement for companies to report on gender pay gaps by proving gender specific wage statistics, find that the legislative step could be a promising new avenue for closing the gap.

Effect of 2006 legislation analyzed

The researchers examined wage statistics of companies prior to, and following, the introduction of Denmark’s 2006 Act on Gender Specific Pay Statistics’ which obligates companies with more than 35 employees to report on gender pay gaps. In order to fully comply to the new transparency law, firms additionally needed to have at least ten men and ten women within a given occupation.

They analyzed data from 2003 to 2008 and focused on companies with 35-50 employees and compared their pay data with identical information from a control group of firms with 25-34 employees – firms of a similar size but that were not required to release gender-segregated data.

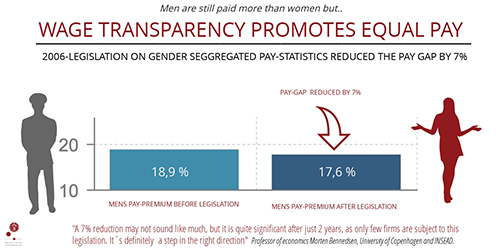

The firms in the analyses paid their male employees a 18.9% wage premium before the regulation was introduced, which is statistically significant for both firms that complied to the legislation and those who did not. The researchers ensured that this difference in men’s and women’s pay was not driven by differences in demographics, work experience, macro trends or selection into specific occupations.

After the regulation the researchers found that the gender pay gap had shrunk 7% in the approximately 1000 Danish firms governed by the new 2006-legislation relative to the control firms, that were not required to publish pay statistics.

- For the first time we are able to document, that pay-transparency really works. A 7% reduction in the pay-gap may not sound impressive, but given the fact that only a limited number of firms in Denmark are governed by this legislation the effect is significant. We can even prove the effect amongst firms, that were not required to provide gender segregated pay-statistics. We know now that wage-transparency works and it is a measure that can be applied nationally as well as internationally. So from this point, it is really just a question of whether or not the politicians actually wish to do something about the pay-gap between men and women, says Professor of Economics Morten Bennedsen, University of Copenhagen and INSEAD global Business School.

Overall wage costs grew slower

Although wages for both male and female employees increased during the period analyzed, the researchers found an overall decline in the wage premium for male employees in firms subject to the legislation, explains Daniel Wolfenzon, Professor of Finance and Economics and chairman of the Finance Division at Columbia Business School.

- What surprised us the most was the way in which this wage gap closed. Women’s wages did not increase at a faster rate in treatment firms as we were expecting. Instead, we find that men’s wages in treatment firms grew slower relative to men’s wages in control firms As a result, the total wage bill grew slower in firms that were required to report wage segregated statistics, says Daniels Wolfenzon.

Experimental literature has shown that men on average are better at negotiating wages than most women, and that they are comfortable asking for high salaries and bonusses.

- But disclosure of wage statistics makes the gap between men´s and women´s pay very transparent to the outside world, and it seems that this makes firm managers able to halt exorbitant pay claims from male employees, says Morten Bennedsen.

More women hired and more women promoted

The researchers additionally found, that the reduction in the pay gap between men and women varied greatly between different types of firms. The reduction in the wage gap was bigger in firms where company executives themselves have more diverse families – especially if they have more daughters than sons. This was also the case in industries that had larger wage gaps prior to the legislation.

The 2006-pay transparency legislation also seems to have a couple unintended gender-related consequences: Firstly, firms included in the legislation hired 4% more women in the intermediate and lower hierarchy levels than control firms, suggesting firms are able to attract more female employees in positions where they offer higher wages. Other spillover effects appear to be, that more women were promoted from the bottom of the hierarchy to more senior positions, after the implementation of the law, while researchers found no significant change in promotions for male employees.

- What is interesting is that the law has unintended consequences on women’s ability to climb up the corporate ladder and their willingness to join the labor market. When firms adopt more fair wage practices towards women, this can have positive effects on women’s labor market outcomes that go well beyond pay gaps, says Assistant Professor of Finance Elena Simintzi at the University of North Carolina.

A few negative consequences of the legislation found by the researchers include a 2.5 percent decline in productivity in the affected firms. But with the simultaneous 2.8 percent reduction in the firms’ total wage costs, there was no significant effects on overall firm profitability.

- We can't tell for sure, why we see this decline in firm productivity. It could be that information on gender pay gaps simply lowers job satisfaction for female employees who find out, that they are paid below their reference group, or because male employees are dissatisfied with not getting the wage increases, they ask for, says Margarita Tsoutsoura, Associate Professor of Finance, Cornell University.

Topics

Related News

Contact

Daniel Wolfenzon

Stefan H. Robock Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia Business School and National Bureau of Economic Research

Mail: dw2382@gsb.columbia.edu

Morten Bennedsen

Niels Bohr Professor, Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

and André and Rosalie Hoffmann Professor, INSEAD, France

Mail: mobe@econ.ku.dk

Phone: +33 673 984134

Elena Simintzi

Assistant Professor of Finance, Kenan-Flagler Business School, University of North Carolina

Mail: Elena_Simintzi@kenan-flagler.unc.edu

Phone: + (919) 962-8992

Margarita Tsoutsoura

John and Dyan Smith Professor of Management and Family Business, SC Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University and National Bureau of Economic Research

Mail: tsoutsoura@cornell.edu

Phone: +1(607) 255-9351

The analysis

Read a pre-print of the analysis here: