Infants are not egocentric: Trust other people's attention more than their own

Babies rely on other people to look after them. New research shows that eight-month-old infants also rely more on other people’s attention than on their own observations.

Children are often perceived as egocentric – and not without good reason. For example, it is well documented that three-year-old children only use their own perspective when predicting someone else's actions. Adults also find it difficult to disregard theirs when empathising with other people. Our egocentric tendencies continue throughout our life.

However, the story is different when it comes to infants. This is shown in a new research project from the University of Copenhagen, where researchers have studied the ability of eight and twelve-month-old infants to remember the location of a moving object.

The aim of the project is to test a theory that early in infancy there is a so-called altercentric bias: The infant trusts other’s observations more than their own.

Follows the attention of other people

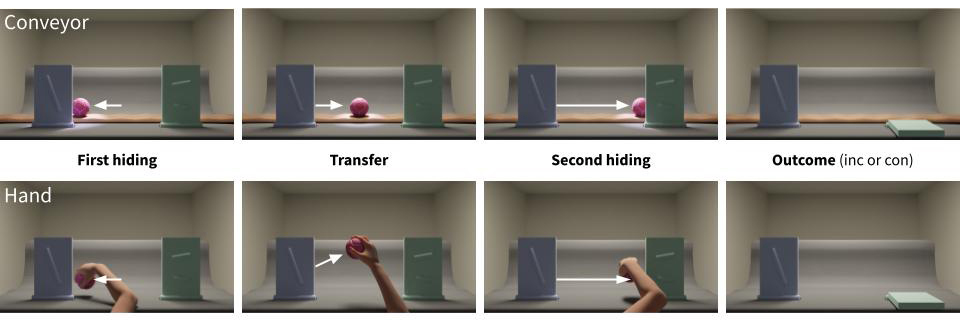

First, the researchers investigated whether infants as young as eight months can remember the location of an object if it is moved from one hidden location to another. To do this, the researchers used an animation showing a conveyor belt or a hand moving a ball behind one screen and then behind another screen.

"When we then reveal either location as empty, the children look longer at the place where the ball should be. This shows us that the children have a memory of where the object moved to," says Velisar Manea, postdoc at the Department of Psychology, who led the research project.

In the initial trials, eight-month-old children had to follow a ball being moved by either a conveyor belt or a hand. In both cases, the children were able to figure out where the ball should be, even if it was mysteriously missing.

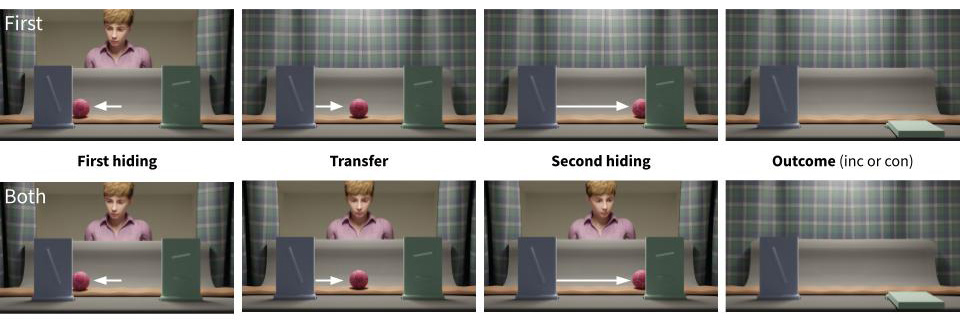

To investigate how the attention of others affects infants' memory, the researchers then conducted an experiment in which an animated human character also followed the movement of the ball.

"While the ball is being transported to its first location, the animated character looks at the ball. Then we cover the character and the infants are left alone to watch the movement of the ball to the second location," explains Velisar Manea and continues:

"As predicted, babies expected to see the ball in the first location, even though they had seen it being moved to the second location. They prioritised the animated agent's attention to what they saw afterwards."

The research team conducted a control experiment where the animated agent follows the ball's location from start to finish.

"To our surprise, infants looked equally to both revealed locations in this experiment. Once again, the eight-month-olds possibly expected the ball on both locations, as the agent attended both" says Velisar Manea.

In the next trials, the infants were put through a similar experiment, but the movement of the ball was fully or partially followed by an animated human. Here, the children's attention was dependent on the character's gaze when judging where the ball was.

Self-confidence grows

But when does the child start to trust their own observations? The research team investigated this question by conducting similar experiments with 12-month-old children.

"Unlike the eight-month-old children, the 12-month-olds were able to remember the last position of the ball in the experiment, where the agent also saw the final location," says Velisar Manea.

In contrast, when the agent only saw the ball in the first hiding location, but the babies saw the transfer to the final location alone, they looked equally to both places.

"This suggests that 12-month-old children are in a transitional phase, where some infants are less affected by the perspective of others, while others are still strongly influenced," says Velisar Manea.

So why is the infant's memory built to initially rely more on the observations of the people surround it – and then later become more independent?

"We think that the altercentric bias facilitates the child's learning at a unique time in life when motoric immaturity limits the infant’s interaction with the environment," Velisar Manea suggests.

Facts about the study

The research project is called "An initial but receding altercentric bias in preverbal infants' memory" and has been published in the scientific journal "Proceedings of the Royal Society B".

Behind the project are cognitive scientists Velisar Manea, Dora Kampis and Victoria Southgate from the University of Copenhagen, Charlotte Grosse Wiesmann from Max Plank Institute in Leipzig, and Barbu Revencu from the Central European University in Vienna.

Contact

Velisar Manea

Postdoc

Department of Psychology

Mail: vem@psy.ku.dk

Phone: +45 60 90 66 03

Dora Kampis

Assistant Professor, Tenure Track

Department of Psychology

Mail: dk@psy.ku.dk

Phone: +45 35 33 39 85

Victoria Southgate

Professor

Department of Psychology

Mail: victoria.southgate@psy.ku.dk

Phone: +45 35 33 43 40

Simon Knokgaard Halskov

Press and communication officer

Faculty of Social Sciences

Mail: sih@samf.ku.dk

Phone: +45 93 56 53 29