Cleaner air in the classroom

SIMON WESTERGAARD LEX, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY

SIMON WESTERGAARD LEX, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY

Smart Cities Accelerator

In 2016, researchers from the Technical University of Den-mark (DTU) and the University of Copenhagen started a three-year joint research project called Smart Cities Accelerator in collaboration with a number of local councils in Denmark and Sweden.

In 2016, researchers from the Technical University of Den-mark (DTU) and the University of Copenhagen started a three-year joint research project called Smart Cities Accelerator in collaboration with a number of local councils in Denmark and Sweden.

The aim of the research is to examine how sustainable energy systems can be opti-mized, creating better indoor climates in public buildings.

The researchers kicked off the project by looking at primary and secondary schools in Høje Taastrup: The indoor climate in class-rooms is crucial for the well-being of both teachers and students and can even affect how much students actually get out of the teaching. As well as emitting unnecessary amounts of CO2, high energy consumption in a school constitutes an expensive item on the council’s annual budget.

The idea behind the project Smart Cities Accelerator is to get statisticians, computer scientists and building engineers from DTU Compute and DTU Byg to work together with lawyers and anthropologists from the University of Copenhagen and with a number of local councils in the Øresund region. The research project is scheduled to be completed in 2019, but already 18 months into the work, it has resulted in considerable im-provements in the schools hosting the project.

Method

In the first part of the project, researchers investigated the buildings and the way the buildings were being utilised at two different schools. Engineers carried out technical studies of the schools’ energy systems and indoor climates. This work involved setting up 70 sensors around the classrooms and offices in order to measure the CO2, temperature, hu-midity and noise levels.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen’s Faculty of Law advised the team on data surveillance, and the anthropologists carried out fieldwork among students, teachers, technical service staff (caretakers), school managers and council employees, and compiled information about how children and staff understood and addressed the buildings' energy consumption.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen’s Faculty of Law advised the team on data surveillance, and the anthropologists carried out fieldwork among students, teachers, technical service staff (caretakers), school managers and council employees, and compiled information about how children and staff understood and addressed the buildings' energy consumption.

Anthropologists also sat in on classes - especially in the older classes - to observe how students experienced the indoor climate and how they resolved disagreements about, for example, ventilation and noise. They mapped the organizational structures and logged the council decisions which directly or indirectly affected how teaching was planned and organised and which had an impact on day-to-day life at the schools.

Results

From analysing the technical data from the schools, it quickly became evident that the concentration of CO2 in the air in a number of classrooms was too high, and this was having a negative impact on students' ability to concentrate. In some classrooms, it was too hot in summer and too cold in winter, which led to arguments among teachers, students and service staff and shifted the focus away from teaching.

Working with anthropologists gives us technical researchers at DTU Compute a completely new perspective on things. Before we started working together with UCPH Anthropology, it never really occurred to us just how important it is to understand the organizational and human aspects in, for example, a local council when we want to develop technical solutions that can actually be applied and accepted in practice. So the anthropological side is an important element in this project and will be for many of our future projects.

The buildings' control systems did not function very efficiently, making it difficult for the schools’ technical staff to get a clear over-view of the buildings' ventilation, heating, cooling and domestic water systems. They therefore found it difficult to solve any prob-lems arising with the indoor climate.

The anthropologists’ field studies among children and staff in the schools showed how a building’s indoor climate can be perceived differently from person to person. Even though the inner climate of a room seems to be a very obvious thing which has a major bearing on people’s comfort and well-being, it is nevertheless a somewhat elusive concept, often making it difficult to "negotiate" in groups.

The issue of indoor climates - is it too hot or too cold, is it too noisy - is something that is discussed and argued about on a daily basis. But when everyone has their own individual view on what the ideal indoor climate should be, it is difficult - especially for decision-makers in the council - to clearly establish that there is a poor indoor climate in a given building. That "someone" at a school "thinks it’s too cold" or there have been "a number of complaints about poor air quality" do not really constitute compelling arguments when the council has to decide which buildings they will spend money on improving.

The researchers therefore took it upon themselves to develop tools and methods which staff at the schools - and in the longer term also students - can use to come to a common understanding about a building’s indoor climate. This will provide local politi-cians with a more robust and objective basis for making decisions when allocating funds to renovate school buildings.

It is inspiring to work together with schools and local councils to tackle these kinds of practical challenges. It gives me a real kick when our research can actually be applied in practice and utilised directly by people working in councils and schools. Even better when it makes good sense and helps to make a real difference.

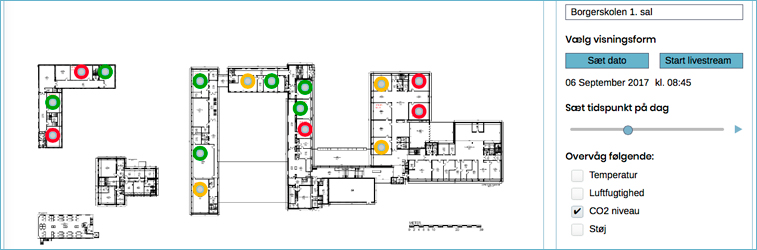

The tool the researchers came up with be-came the website www.skoleklima.dk, which is currently being trialled at one of the schools. The website is the result of the re-searchers collating and compiling the data they have collected so that users can log in and track a building's CO2, temperature, noise and humidity levels. It gives teachers and students the opportunity to improve the indoor climate (e.g. by opening a window) when they see, for example, that CO2 levels are too high. The website also gives the schools’ technical staff an overview of the buildings' consumption and current condition, so they can quickly adjust the ventilation or the temperature in rooms where the climate is poor.

Working together with the universities’ researchers also gave the local council the confidence to invest in renovating school buildings, which immediately improved the indoor climate for students and staff alike.

More specifically, the questions raised by the researchers and the continuous results of the measurements prompted the council’s building department to upgrade the school’s ventilation system so that it delivers more fresh air into the classrooms and makes it quicker and easier to find faults in the buildings' energy systems.

Further research

Smart Cities Accelerator will continue up until September 2019, and the researchers are now working with teachers and council employees to develop school-related activities for the website www.skoleklima.dk which teachers can use in their classes to teach students about, for example, technology, data, energy and sustainability. Here the students can carry out experiments in the buildings and with the technological systems that are already a part of their school life. Later, the researchers will test out the website www.skoleklima.dk in other schools in Denmark and Sweden.

Website www.skoleklima.dk

In 2018 information compiled about indoor climates and energy consumption in public buildings was tested among teachers, students, service staff, etc. in schools and in Høje Taastrup council.

Facts about Smart Cities Accelarator

- An interdisciplinary research project focusing on sustainable change.

- Collaboration between DTU and the University of Copenhagen and 10 local councils in the Capital Region of Denmark and Region Skåne in Sweden.

- Project period: 1 September 2016 - 1 September 2019

- Budget: approx DKK 48 million.

See more on: https://smartcitiesaccelerator.eu